New Delhi, Dec 8 (IANS) The persecution of journalists by the state is a grim reality across many authoritarian regimes—from Taliban-ruled Afghanistan to Myanmar, Belarus, Turkiye, and the Philippines. In such contexts, the press—often deemed the “fourth pillar of democracy”—is treated not as a watchdog, but as a threat. Bangladesh is also echoing this global trend.

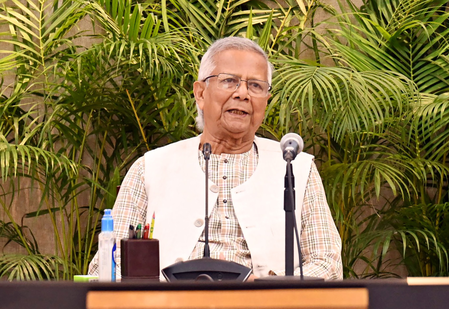

After the fall of the Sheikh Hasina government on August 5, 2024, many viewed the rise of Nobel Laureate Dr Muhammad Yunus as a turning point. Backed by student protests and public sentiment, his appointment as Chief Adviser cum Prime Minister of the interim government was seen as a symbolic “second liberation,” especially for the country’s long-suffocated media.

But within months, that promise gave way to disillusionment. Despite initial pledges to restore freedom of expression and uphold democratic values, Yunus’s administration has presided over a deepening assault on press freedom. Journalists, both in urban and rural areas, are now facing threats, fabricated charges, detentions, and brutal attacks. Old laws like the Digital Security Act— once condemned by Yunus himself—remain in force. New regulations, framed in the name of “digital safety,” risk further gagging the media.

More troubling still, the government has failed to announce an election date, turning its “interim” status into a prolonged, unaccountable rule. Institutions meant to safeguard democracy have fallen silent or become enablers of repression. The optimism of August has morphed into fear, as the Yunus regime retools authoritarian tactics under the guise of reform.

In one year, the Yunus-led government has systematically undermined media freedom in Bangladesh. And hope has curdled into control, and the dream of a freer, more democratic society is slipping further away with each passing day. Behind the laurels lies a familiar hand of repression.

A Dangerous Time for Free Expression

Freedom of speech, a foundational pillar of democracy, remains under severe threat. Journalists—especially those from minority communities—are facing escalating violence, legal harassment, and coordinated state-backed intimidation.

A report released on World Press Freedom Day 2025 paints a bleak picture: within eight months of Dr Yunus taking office, at least 640 journalists were targeted. Of these, 182 faced criminal cases, 206 experienced violence, and 85 were placed under financial scrutiny by the Bangladesh Financial Intelligence Unit.

The attacks are not isolated; they are systemic, deliberate, and widespread. From legal persecution to outright physical violence, the Yunus regime has transformed Bangladesh into one of the most dangerous places in Asia to be a journalist.

Violence against journalists has become commonplace. In March 2025, two journalists were attacked at Barishal Court, while others were assaulted in Dhaka and outside the Dhaka Reporters’ Unity. The most horrific incident came on March 18, when a woman journalist was gang-raped in Dhaka—a case that drew international outrage, including condemnation from ARTICLE 19 and other watchdogs.

In April, New Age’s Rafia Tamanna and Daily Prantojon’s Sajedul Islam Selim were physically attacked. Offices of news outlets were vandalised. Prothom Alo, a paper accused of being an “agent of India,” saw its Rajshahi office destroyed. These attacks illustrate a dangerous trend: the delegitimisation of critical voices through nationalist propaganda followed by violent suppression.

Legal harassment has become a preferred tool to silence dissent. Journalists are being dragged into courtrooms and prisons over flimsy or fabricated charges. Kamruzzaman, a journalist in Satkhira, was sentenced to 10 days in jail by a mobile court for “obstructing government work.” His real crime? Reporting on poor construction work.

Rubel Hossain of Dhaka Mail was falsely implicated in a murder case related to student protests. Three prominent journalists—Naem Nizam, Moynal Hossain Chowdhury, and Syed Burhan Kabir—faced arrest warrants under the much-criticised Digital Security Act. Their only fault: publishing content critical of powerful figures.

The State vs. Media Institutions

Media institutions haven’t been spared either. An adviser at the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting announced audits targeting “opposition-affiliated” media houses—a move widely viewed as financial intimidation.

Deepto TV suspended its news broadcasts following political backlash. ATN Bangla dismissed a reporter for merely raising a sensitive question. In both cases, official denials of state interference were undercut by obvious patterns of state-orchestrated pressure.

In a disturbing episode on May 4, journalists at Daily Janakantha protesting unpaid wages were assaulted by goons reportedly linked to the National Citizen Party. This convergence of financial abuse and physical violence has created a stifling environment for critical media.

The Yunus government has done little to allay fears about surveillance and data privacy. Instead, it has doubled down with proposed legislation like the Cyber Protection Ordinance 2025 and the Personal Data Protection Ordinance—laws that could further institutionalise censorship and mass surveillance.

With travel bans imposed on more than 300 journalists, and bank accounts frozen for over 100 of them, the message is clear: dissent will be crushed not just with batons, but with bureaucracy.

Journalists from minority communities are bearing the brunt of the crackdown. Shyamol Dutta, a leading Hindu journalist and editor of Bhorer Kagoj, was jailed after being removed from his post at the National Press Club. Munni Saha, a prominent media personality, is facing several cases and has been detained for questioning.

More than 50 minority journalists are reportedly living in fear, with many dismissed from their jobs under opaque circumstances. This pattern reflects not just a press freedom issue, but an assault on the fundamental rights of minority communities.

Targeting Prominent Figures and Media Houses

The arrest of top media professionals like Mozammel Babu, CEO of Ekattor TV, and Syed Ishtiaq Reza, former chief of news at GTV, has shocked the industry. The charges—often murder or conspiracy—lack credibility, pointing to a larger political agenda.

In one bizarre move, a complaint filed with the International Crimes Tribunal accused 29 journalists and editors, alongside former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, of spreading “false news to justify genocide.” The charges are outrageous and serve no purpose but to stoke fear and paralyse the press.

Even high-profile reporters like Shahnaz Sharmin, known for her fearless on-the-ground reporting, have been named in criminal complaints. Her alleged involvement in the death of a protester is widely seen as a fabricated effort to tarnish her reputation.

Dr Yunus’s rise to power was framed as a “second liberation.” His global reputation as a humanitarian and social entrepreneur gave many hope. But the honeymoon was short-lived. The arrest, torture, and surveillance of journalists under his watch signal a complete betrayal of those ideals.

Rather than dismantling the oppressive tools of the previous regime, the interim government has inherited and expanded them. Laws are being used as weapons. The courts have turned into instruments of intimidation. And civil liberties—once hoped to be restored—have only deteriorated.

Despite the dire situation, there are glimmers of resistance. A Media Reform Commission, proposed by information adviser Nahid Islam, offers a chance for dialogue and reform. But unless these proposals are translated into immediate action—starting with the release of unjustly detained journalists and withdrawal of politically motivated cases—the initiative risks becoming another empty gesture.

Civil society must stay vigilant. International watchdogs, human rights organisations, and democratic governments must increase pressure on the Yunus administration. Silence is not neutrality—it is complicity.

The Fight for Truth Must Go On

In the last 12 months, Bangladesh has moved from the promise of change to the peril of authoritarianism. The interim government led by Dr Muhammad Yunus was expected to restore justice, transparency, and democratic values. Instead, it has turned against the very institutions and individuals that form the backbone of a functioning democracy—the free press.

The persecution of journalists, the weaponisation of laws, the sidelining of minority voices, and the unending delay of elections paint a grim portrait of a government losing legitimacy by the day. If Yunus does not act swiftly to reverse this trend, he risks eroding not only his reputation but also the democratic foundation of the country.

Bangladesh’s journalists are not just chroniclers of events—they are defenders of democracy, truth, and public interest. Silencing them will not silence the truth. It will only delay the reckoning. The time for reform is now—before the darkness of repression becomes permanent.

(Dr Sreoshi Sinha is a Senior Fellow Centre for Joint Warfare Studies (CENJOWS), while Abu Obaidha Arin is a student at the University of Delhi.)

–IANS

Int/scor/uk